The Iroquois Theatre Fire: A Forgotten Tragedy That Changed Fire Safety Forever

On December 30, 1903, Chicago witnessed one of the worst disasters in its history, and the deadliest theatre fire in the United States. Chicago's early history is unfortunately rife with fire incidents, and this would occur just over three decades following the Great Chicago Fire.

The theater was located at 26 W Randolph St in Chicago, on the site where the James M. Nederlander Theatre now exists today.

The Iroquois Theatre, a lavish and modern venue that opened just a month before, was packed with more than 1,700 people, mostly women and children, who came to see a matinee performance of the musical comedy Mr. Bluebeard.

Little did they know that a spark from a stage light would ignite a fire that would engulf the theatre in minutes, trapping and killing over 600 people in a horrific scene of panic, chaos, and carnage.

| The Iroquois Theater before the fire. (Unknown photographer) |

The Iroquois Theatre was built on the site of the former Hooley’s Theatre, which itself was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire and relocated to the Randolph site. The new theatre was designed by Benjamin Marshall and Charles Fox, two prominent architects who wanted to create a state-of-the-art and luxurious entertainment venue for Chicago’s growing and affluent population.

The theatre had a capacity of 1,602 seats, but could accommodate up to 2,000 people with standing room. It boasted a stunning interior, with a grand lobby, a marble staircase, a dome ceiling, and elaborate decorations. It also claimed to be “absolutely fireproof”, with fireproof materials, asbestos curtains, iron doors, and fire exits.

However, behind the facade of elegance and safety, the Iroquois Theatre was riddled with fire hazards and code violations. Some of these were known by city officials, who failed to enforce the regulations or inspect the theatre before its opening. Some of the major flaws of the theatre included:

The asbestos curtain, which was supposed to prevent the fire from spreading from the stage to the auditorium, was defective and snagged when lowered.

The fire exits were locked, hidden, or blocked by metal gates, to prevent patrons from sneaking into better seats or leaving without paying.

The exit doors opened inward, instead of outward, making them impossible to open when the crowd pushed against them.

The theatre had no fire alarm, sprinkler system, or fire extinguishers. There was also no telephone or fire alarm box to call for help.

The theatre was overcrowded, with hundreds of extra people standing in the aisles and stairways, creating a bottleneck for escape.

The theatre had flammable decorations, such as muslin curtains, paper flowers, and wooden scenery, that fueled the fire.

The Fire: “From Mimicry to Tragedy”

The fire broke out at about 3:15 p.m., during the second act of Mr. Bluebeard. A broken arc lamp ignited some muslin curtains near the stage, creating a small flame that quickly grew out of control. The stagehands tried to put out the fire with a primitive retardant, but it was ineffective. The actor Eddie Foy, who played the lead role of Mr. Bluebeard, tried to calm the audience and ordered the orchestra to keep playing. He also called for the asbestos curtain to be lowered, but it got stuck halfway, leaving a gap for the fire to spread.

The audience, realizing the danger, panicked and rushed for the exits. However, they found most of them locked, hidden, or inaccessible. The few exits that were open were jammed with people, who trampled, crushed, or suffocated each other in their desperation. Some people jumped from the windows or the fire escapes, risking injury or death. Some people stayed in their seats, hoping for rescue, but were burned alive or asphyxiated by the smoke.

|

| Illustration of the fire. (Memories of the Prairie) |

The fire was so intense that it created a backdraft, a sudden explosion of air and flames, when a rear stage door was opened by the cast members. The backdraft swept through the theatre, killing many people instantly, especially in the upper balconies. The fire also reached the lobby, where more people were trapped and killed.

The fire department arrived at the scene, but was hampered by the lack of water pressure, the narrow streets, and the icy conditions. They also had no way of communicating with the theatre staff or the police, who were overwhelmed by the chaos. It took about half an hour to bring the fire under control, but by then, it was too late for most of the victims.

The Iroquois Theatre fire was a national tragedy, that shocked and saddened the country. The official death toll was 602, but some estimates put it as high as 800. Most of the victims were women and children, who had come to enjoy a holiday show. Many families lost their loved ones, and many children were orphaned. The bodies of the victims were taken to makeshift morgues, where relatives and friends searched for their missing ones. The scenes of grief and horror were indescribable.

To put the tragedy into modern context, the fire was the deadliest single-building disaster in US history for nearly 100 years before the September 11th attacks in 2001.

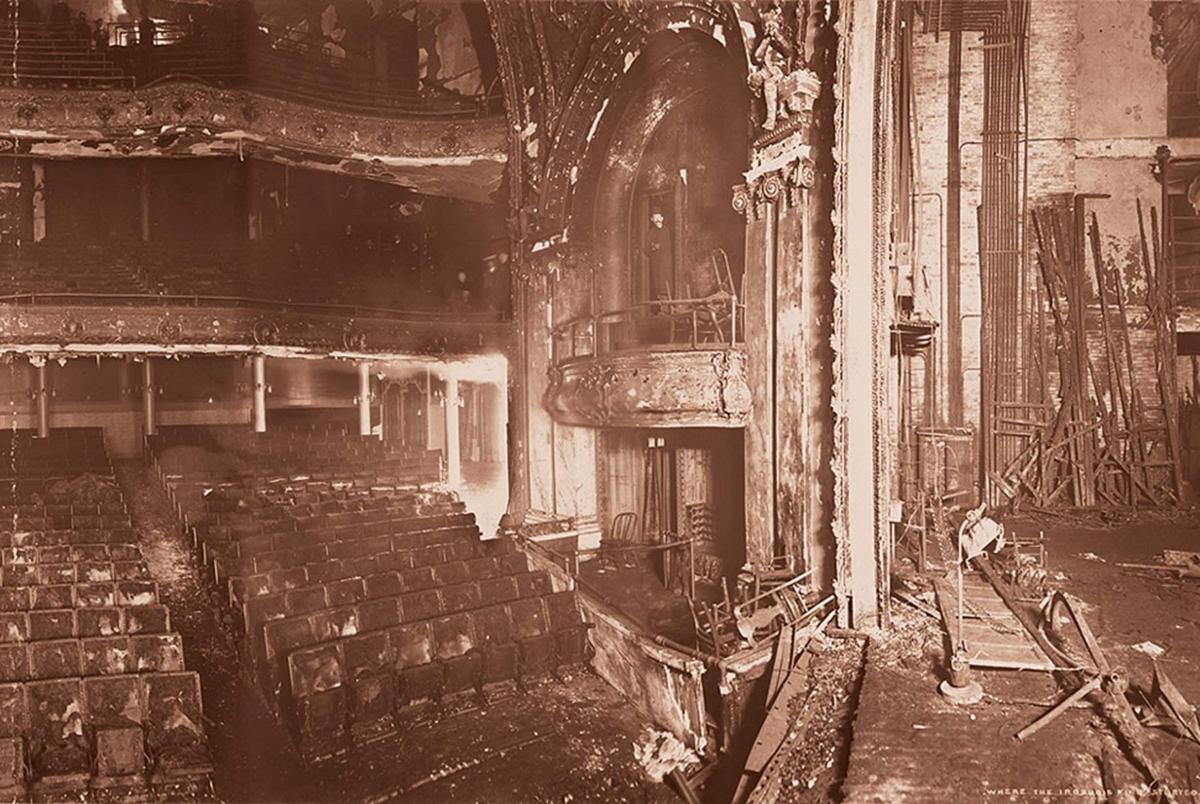

|

| Aftermath of the fire. |

The fire also sparked a public outcry and a demand for justice. The city officials, the theatre owners, the architects, the contractors, and the performers were all blamed for the disaster. Several investigations, lawsuits, and trials were launched, but none resulted in any convictions or significant penalties. The theatre was closed and later demolished, and a new building was erected on its site.

However, the fire also led to some positive changes, especially in the field of fire safety. The fire exposed the flaws and corruption of the city’s building codes and enforcement, and prompted a series of reforms and improvements. Some of the new measures included:

The installation of fire alarms, sprinklers, extinguishers, and telephones in public buildings.

The requirement of exit signs, emergency lighting, and fire drills in theatres and schools.

The design of exit doors that open outward, and the prohibition of locking or blocking them.

The use of fire-resistant materials and curtains in theatres and stages.

The regulation of theatre capacity and seating arrangements.

The invention and adoption of the panic bar, a device that allows doors to be opened easily by pushing on a horizontal bar.

These reforms saved countless lives in the future, and influenced the fire safety standards and codes in other cities and countries. The Iroquois Theatre fire also inspired the creation of the Iroquois Memorial Hospital, a non-profit hospital that served the community until 1951. The city of Chicago also held an annual memorial service for the victims, until the 1960s.

|

| "The Burning Iroquois" Sheet Music. Written in memory of the fire of the Iroquois Theatre, Chicago, December 30, 1903. BGSU Library |

Comments

Post a Comment