The Transcontinental Railroad: 150 Years Later

The 150th Anniversary of the completion of the original transcontinental railroad occurred on May 10th, 2019. In honor of the anniversary, there were many events going on, including a re-enactment of the event, and Union Pacific firing up their "Big Boy" engine, UP 4014, which visited West Chicago a few weeks after the fact.

Likewise, today I'm going to talk about this momentous occasion. UPDATE: Since I wrote this blog in 2019, Union Pacific has created a fantastic visual story map about the Transcontinental that you should check out, after reading my blog of course.

Through a very cynical lens, one could consider the Original Transcontinental Railroad the ultimate marketing gimmick in the 1860's, for a nation yearning for unity and technological advancement just a few years after a bloody Civil War.

The Transcontinental never came close to traversing the continent, it was actually made of three railroads, and ran roughshod over cost estimates, in part because of corporate greed and government waste. This side of the completion of the line was discussed in Richard White's Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America.

Likewise, today I'm going to talk about this momentous occasion. UPDATE: Since I wrote this blog in 2019, Union Pacific has created a fantastic visual story map about the Transcontinental that you should check out, after reading my blog of course.

| |

|

|

| An 1868 map showing the completed Transcontinental Railroad, which would become a reality the year after. Image: Cornell University |

Even when the "last" spike was driven into the ground at Promontory, those wishing to traverse from San Francisco to Council Bluffs would have to use ferries on either end of the route, as the Union Pacific Missouri River Bridge wouldn't be complete until 1872.

|

| Image via Union Pacific |

And yet, the driving of the Golden Spike and "completion" of the route would be the most iconic event in 1860's American railroad history, and would be a catalyst for economic and territorial expansion in the West. But regardless of its shortcomings and cost, it ultimately cut what would have been a months-long journey across the United States into a span of a few days, connecting both coasts of the country at a time just after the Civil War when such interconnections were necessary to preserve the Union.

Construction:

The Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 created two railroad companies, the Central Pacific Railroad in the West, and the Union Pacific Railroad in the Midwest. It asked for “men of talent, men of character, men who are willing to invest” in developing the nation’s first transcontinental rail line. (US Senate)

A book on the plight of these workers, called Ghosts of Gold Mountain tells their story. "By 1867, construction reached Cheyenne, WY. On the Central Pacific side, thousands of Chinese workers were brought in to aid in construction, and eventually much of the labor was done by these workers. The contributions of these workers have in many respects been glossed over in history, but events are planned to include their story in the festivities of the 150th anniversary."

Operation:

Proposal

The first of what would become many transcontinental railroad proposals was in 1832, when Dr. Hartwell Carter proposed a Lake Michigan to Pacific Ocean route via Oregon. He sent a fully-proposed route fifteen years later in 1847. Although railroads were a new technology, Congress supported the idea of expanding the fledgling American railroad network west, and commissioned surveys for possible routes during the 1840's-50's.

These surveys wound up being quite useful in learning the geography, flora and fauna, and history of the West, but failed to give a real good idea on a route a still-hypothetical transcontinental railroad should take.

These surveys wound up being quite useful in learning the geography, flora and fauna, and history of the West, but failed to give a real good idea on a route a still-hypothetical transcontinental railroad should take.

The northern route proposal had issues with snow in the winter, which still persist to this day, while a southern route would have to go the southern parts of New Mexico and Arizona, through what was Mexican territory in the 1840's. The Gadsden Purchase would resolve this issue, and such a route was completed by Southern Pacific in the 1880's.

|

| The proposed "Southern Route" which eventually became the Southern Pacific Railroad. |

The political differences between the North and South United States also played a role in route choice, but when the Southern States seceded to form the Confederacy, it was easy to pass the Pacific Railroad Act by the remaining legislature. A central line starting at Council Bluffs, IA was chosen as the beginning of what would become the Union Pacific Railroad.

Construction:

The Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 created two railroad companies, the Central Pacific Railroad in the West, and the Union Pacific Railroad in the Midwest. It asked for “men of talent, men of character, men who are willing to invest” in developing the nation’s first transcontinental rail line. (US Senate)

The routes would begin in Sacramento, California and Council Bluffs, Iowa, respectively. Another issue was what gauge the railroad would be, it was decided upon the 4'8 1/2" gauge, which would become the standard throughout the United States during the construction of the line. The act was amended in 1864.

Railroad bonds and land grants were issued for both lines, and no single entity was to own more than 10 percent of the stocks of either company. One of the largest financiers of the line was Brigham Young, who also provided construction workers from his ranks in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. However, the companies themselves also established smaller companies in order to circumvent this requirement and make more profit for themselves.

Civil Engineers from the Civil War, Canada, and Britain were called in to build bridges and design the structures necessary from the line. Materials were generally transported from the Eastern US via ships, around the coast of South America at the Isthmus of Panama, where they were transported via land to the Pacific Ocean via the Panama Railroad, as the Panama Canal was still a half-century away. Wood was generally harvested from California and other forested areas along the route.

On January 8th, 1863, the Central Pacific broke ground in the west. The Union Pacific wouldn't break ground until 1865, as it was more difficult for them to find workers and material as a result of the Civil War. Even after the war, the South's railway network required rebuilding, which created competition for material. As such, UP only completed 40 miles of track to Fremont, NE in its first year.

Railroad bonds and land grants were issued for both lines, and no single entity was to own more than 10 percent of the stocks of either company. One of the largest financiers of the line was Brigham Young, who also provided construction workers from his ranks in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. However, the companies themselves also established smaller companies in order to circumvent this requirement and make more profit for themselves.

Civil Engineers from the Civil War, Canada, and Britain were called in to build bridges and design the structures necessary from the line. Materials were generally transported from the Eastern US via ships, around the coast of South America at the Isthmus of Panama, where they were transported via land to the Pacific Ocean via the Panama Railroad, as the Panama Canal was still a half-century away. Wood was generally harvested from California and other forested areas along the route.

|

| The Panama Railroad remained the only true Transcontinental Railroad until Canadian Pacific was completed. |

Another issue outside of material, terrain, and cost that the route had to endure was that of the Native American. Conflicts with tribes resulted in the Natives sabotaging the railroad, and attacking white settlements by the line. Tribes who sold their land to the government never envisioned such a change from their way of life that the railroad brought in. The largest conflict was the slaughter of buffalo in the central US as food for construction workers. The US Army stepped in to aid workers from Native American Attacks.

The loss of buffalo from much of the US, numbering only 300 at one point forced Congress to take action, and in doing so, helped create the National Park system we know today. Congress made it illegal to kill any animals or birds within Yellowstone National Park.

By 1867, construction reached Cheyenne, WY. On the Central Pacific side, thousands of Chinese workers were brought in to aid in construction, and eventually much of the labor was done by these workers. The contributions of these workers have in many respects been glossed over in history, but events are planned to include their story in the festivities of the 150th anniversary.

|

| “Cheyenne Indians tearing up the tracks of the Union Pacific R.R.” Courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society via the Mountain West Digital Library. |

|

| Rounding Cape Horn, California. Road to Iowa Hill from the river, in the distance, c 1866. Image: Alfred A. Hart - Union Pacific Museum |

A book on the plight of these workers, called Ghosts of Gold Mountain tells their story. "By 1867, construction reached Cheyenne, WY. On the Central Pacific side, thousands of Chinese workers were brought in to aid in construction, and eventually much of the labor was done by these workers. The contributions of these workers have in many respects been glossed over in history, but events are planned to include their story in the festivities of the 150th anniversary."

Construction would continue at a rampant pace until 1869. On April 28th, 1869, ten miles of track was laid in one day by the Central Pacific in Western Utah by mostly Chinese workers, after a wager between the Central and Union Pacific as to who could lay track quicker.

The Central Pacific ran a locomotive at 40 mph across the newly laid track to prove it was sound. As Union Pacific only had 10 miles of track left to lay themselves, Central Pacific couldn't be beat, prompting one UP official to consider tearing up a few miles track in an attempt to take the record for themselves.

|

| The sign is now on display at the California State Railroad Museum |

Completion

The two railroad lines completed their respective stretch of trackage, and actually crossed one another, building two grades near Promontory in an attempt to extract as much government money as possible.

|

| "Promontory Trestle Work and Engine no. 2" Image: Andrew J Russell |

|

| Roughly 150 years later, this is the same angle east of Promontory, UT where the above trestle once stood. Image: YesterdaysUtah via Instagram |

Union Pacific's grade would be abandoned in 1870 after less than a year of use, and is thus nothing more than a footnote in history to anyone besides abandoned railroad enthusiasts like myself. It should be noted that there were parts of the Union Pacific grade that, once the rails were joined at Promontory, were never finished.

|

| Locations of the UP and CP grades east of Promontory. Google Maps View |

In late 2021, Google released Street View imagery of the area west of Promontory near the USGS Recorder Springs Well that captures the view of both grades and provides a fantastic trip online for those who are unable to hike in the middle of the desert to observe the old grade(s):

|

| December 2021 Google Maps Street View Imagery |

The Golden Spike Ceremony was supposed to take place on the 8th of May, but bad weather pushed it back two days. Leland Stanford, president of the Central Pacific Railroad, and the man who would later found Stanford University was the man who drilled the final spike into the ground, completing the Transcontinental Railroad.

On the 10th, a telegraph message, "D O N E" was transmitted across the United States.

As stated earlier, while this was nonetheless the most impactful construction project of the 1800's, it still wasn't truly a transcontinental railroad. One wishing to connect to the Pacific Ocean still had to take a ferry from Sacramento, as the original Western Pacific Railroad was incomplete (Central Pacific would purchase this line and incorporate it into their network.) In addition, one traveling from, Chicago for example, would still need to take a ferry across the Missouri River from Council Bluffs to Omaha.

The decision to end the route at Council Bluffs in the middle of the United States has had an impact on the rail industry that is still seen today; all of the Class I railroads only serve in the East or West United States. BNSF and Union Pacific serve the Western US, while Norfolk Southern and CSX serve the East, with help from Class II and III railroads. CN in the US only serves the Central US, given its predecessor was the Illinois Central, and Canadian Pacific serves the Upper Midwest via the former Soo Line Railroad.

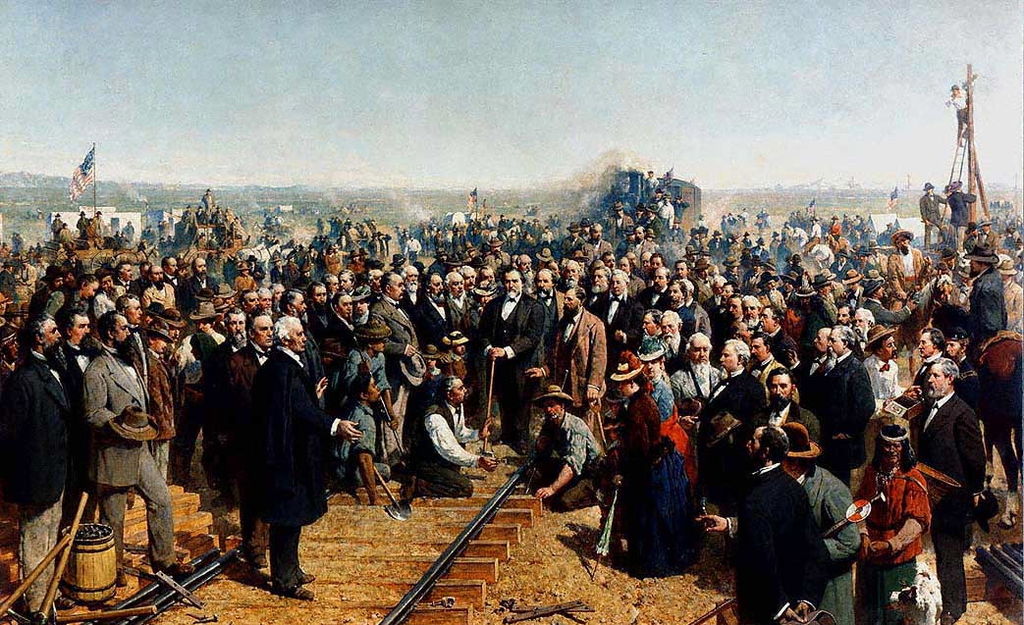

|

| "The Last Spike" By Thomas Hill, 1881. Image via Wikipedia Commons |

The decision to end the route at Council Bluffs in the middle of the United States has had an impact on the rail industry that is still seen today; all of the Class I railroads only serve in the East or West United States. BNSF and Union Pacific serve the Western US, while Norfolk Southern and CSX serve the East, with help from Class II and III railroads. CN in the US only serves the Central US, given its predecessor was the Illinois Central, and Canadian Pacific serves the Upper Midwest via the former Soo Line Railroad.

Operation:

While still much safer and efficient than a six-month journey across the US in a wagon, the earliest iteration of the transcontinental was still treacherous by today's standards. Snow sheds in the Sierra Nevada Mountains had to be built to allow for winter operations. As the emphasis during the construction phase of the project was on speed and not necessarily quality, many bridges and grades along the route had to be adjusted.

By 1876, it was finally possible to travel from New York City to San Francisco in one trip, as on June 4th of that year, the Transcontinental Express left New York and arrived 83 hours and 39 minutes later in San Francisco.

By 1876, it was finally possible to travel from New York City to San Francisco in one trip, as on June 4th of that year, the Transcontinental Express left New York and arrived 83 hours and 39 minutes later in San Francisco.

Abandonment

In 1904, a more direct route (literally) across the Great Salt Lake was completed, called the Lucin Cutoff. This allowed the Southern Pacific (Central Pacific's successor) to shed 42 miles off the Transcontinental Route.

In 1904, a more direct route (literally) across the Great Salt Lake was completed, called the Lucin Cutoff. This allowed the Southern Pacific (Central Pacific's successor) to shed 42 miles off the Transcontinental Route.

|

| Lucin Cutoff at Mid-Lake Station Postcard via eBay |

One the cut-off was completed, the original route was only used for local farming customers and passengers, while mainline traffic used the cutoff. By 1942 however, the original route was abandoned with the rails reclaimed to aid in the effort of World War II. What had originated thanks to a war was also abandoned as a result of war.

Thankfully, Promontory Point became part of the Golden Spike National Historic Park. But the stations of Corrine, Quarry, Balfour, Conner, Lampo (Blue Creek), Surbon, Rozel, Lake, Kosmo, Monument, Nella, Kelton, Peplin, Ombrey, Matlin, Terrace, Watercress, Bovine, and Umbria Junction were all otherwise forgotten. (Abandoned Rails)

Thankfully, Promontory Point became part of the Golden Spike National Historic Park. But the stations of Corrine, Quarry, Balfour, Conner, Lampo (Blue Creek), Surbon, Rozel, Lake, Kosmo, Monument, Nella, Kelton, Peplin, Ombrey, Matlin, Terrace, Watercress, Bovine, and Umbria Junction were all otherwise forgotten. (Abandoned Rails)

|

| A UP excursion train crosses the new Lucin Cutoff. Image: Greg Brubaker via RailPictures.Net |

While the Lucin Cutoff would be the most dramatic re-alignment of the route, it was far from the only one, as significant portions of the original route were upgraded with their trajectories changed, particularly in neighboring Wyoming and Nevada. Another large example of abandonment exists near Donner Pass.

One thing I find particularity interesting about the Transcontinental Railroad, is that exactly 100 years after its completion, Americans would land on the moon, in a mission that took just over eight days. From cutting a cross country trip from months into days, in the 100 years that followed, we used the same amount of time to traverse to a celestial body. What will we be doing in 2069?

I should noted that this isn't a comprehensive history of the line; I left a lot out of this blog. A project as large as this has a history far more reaching than the confines of a blog can offer. In addition, all of the websites credited and linked to from here do a fantastic job in telling the story of the Transcontinental Railroad as well, in their own ways.

For more reading on the Original Transcontinental Railroad, I suggest Empire Express; Building The First Transcontinental Railroad. (Amazon) (eBay)

Thanks for reading!

|

| Graffiti in one of the original tunnels. |

I should noted that this isn't a comprehensive history of the line; I left a lot out of this blog. A project as large as this has a history far more reaching than the confines of a blog can offer. In addition, all of the websites credited and linked to from here do a fantastic job in telling the story of the Transcontinental Railroad as well, in their own ways.

For more reading on the Original Transcontinental Railroad, I suggest Empire Express; Building The First Transcontinental Railroad. (Amazon) (eBay)

it is nice to read some of the history, but like you said how many people care about old rail road tracks.

ReplyDelete